Densely-populated, urban New Jersey cities like Hoboken and Jersey City are closer to Manhattan than many neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens, or the Bronx. Other cities like Newark and Paterson are also significant nodes in the greater metropolitan area. Yet, their transit connections to New York City are not as expansive, usually slower, and often more costly than they should be. This imbalance not only affects regional mobility but inhibits economic growth, vehicle traffic, and quality of life.

The PATH (Port Authority Trans-Hudson) rapid transit system, opened in 1908 and pretty much built to its modern form by the 1930s, comprises a small rail network connecting Newark, Jersey City, and Hoboken with Manhattan. It’s an essential piece of the region’s infrastructure, but it suffers from its limited reach, insufficient frequency, and lack of fare integration with NJ Transit and MTA service.

New Jersey Transit operates many commuter rail lines throughout the state. The commuter rail system, while extensive, is geared toward morning and evening commutes and has limited usefulness outside of peak hours. Trips not involving its major hubs (Midtown, Newark, Hoboken) are inconvenient due to the hub-and-spoke layout of the system. Additionally, aging infrastructure and bottlenecks like the two-track North River Tunnels into Penn Station cause delays and limit capacity.

Northern New Jersey’s bus system is among the busiest and most extensive in the country. It includes local and commuter NJ Transit buses, and a unique network of privately-operated jitney buses along certain corridors. However, buses still have to contend with heavy traffic and outdated infrastructure (like the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Midtown Manhattan). Their high use is less a reflection of their quality and more a symptom of the lack of better alternatives.

Supplementing New Jersey’s commuter and bus networks are the Newark Light Rail and Hudson-Bergen Light Rail (HBLR) systems (both also operated by NJ Transit). They provide important connections to PATH and NJ Transit trains, but are under-utilized due to their limited reach.

As it stands today, many places in northern New Jersey, including Paterson, Elizabeth, and parts of Newark, can be considered high-quality transit deserts. They are not completely without transit — there is usually some combination of bus, commuter rail, or light rail — but they lack the fast, frequent, and affordable options they deserve.

History

Northern New Jersey’s transit connection to New York City has long been shaped by a patchwork of solutions. Long ago, railroads brought passengers to expansive stations along the New Jersey side of the Hudson riverfront, with a ferry ride necessary to continue on to Manhattan and points north and east.

This basic system continued until the early 20th century, at which point the Pennsylvania Railroad built and opened the North River Tunnels that brought trains under the Hudson and directly into Midtown Manhattan. Around the same time, the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (present-day PATH) opened both the Uptown Hudson Tubes and Downtown Hudson Tubes, tunnels which brought rapid transit from points in New Jersey to Midtown Manhattan and Lower Manhattan, respectively.

This basic layout of cross-Hudson transit hasn’t really changed since then. Within New Jersey, Newark’s Light Rail subway opened in 1935 and has seen some incremental additions and improvements (like the Bloomfield and Broad Street extensions) since. The Hudson-Bergen Light Rail (HBLR) was constructed to its current extent in phases between 2000 and 2011, acting as a local connector and supplement to the PATH system in Hudson County.

Alongside official transit service, northern New Jersey has long relied on a vital network of privately-operated jitney buses, which are heavily used among immigrant communities in the region. Jitneys offer highly-frequent bus service along busy corridors like Bergenline Avenue and Route 4. Though they often lack consistent signage or schedules, jitneys have grown to become an indispensable part of northern New Jersey’s transit system, filling gaps left by the official NJ Transit network and serving thousands of riders daily.

Proposal

A more connected, expansive transit system is vital for the region’s long-term growth and prosperity. Every day, hundreds of thousands of people travel between New Jersey and New York City, yet the infrastructure enabling this movement is fragmented, overburdened, and outdated.

Fixing this will facilitate growth, quicken commutes, and help the region feel more connected. Improved transit access can also play a pivotal role in addressing the region’s housing crisis by opening new avenues of growth (via transit-oriented development and economic stimulation) without overburdening existing infrastructure — increasing supply and reducing prices.

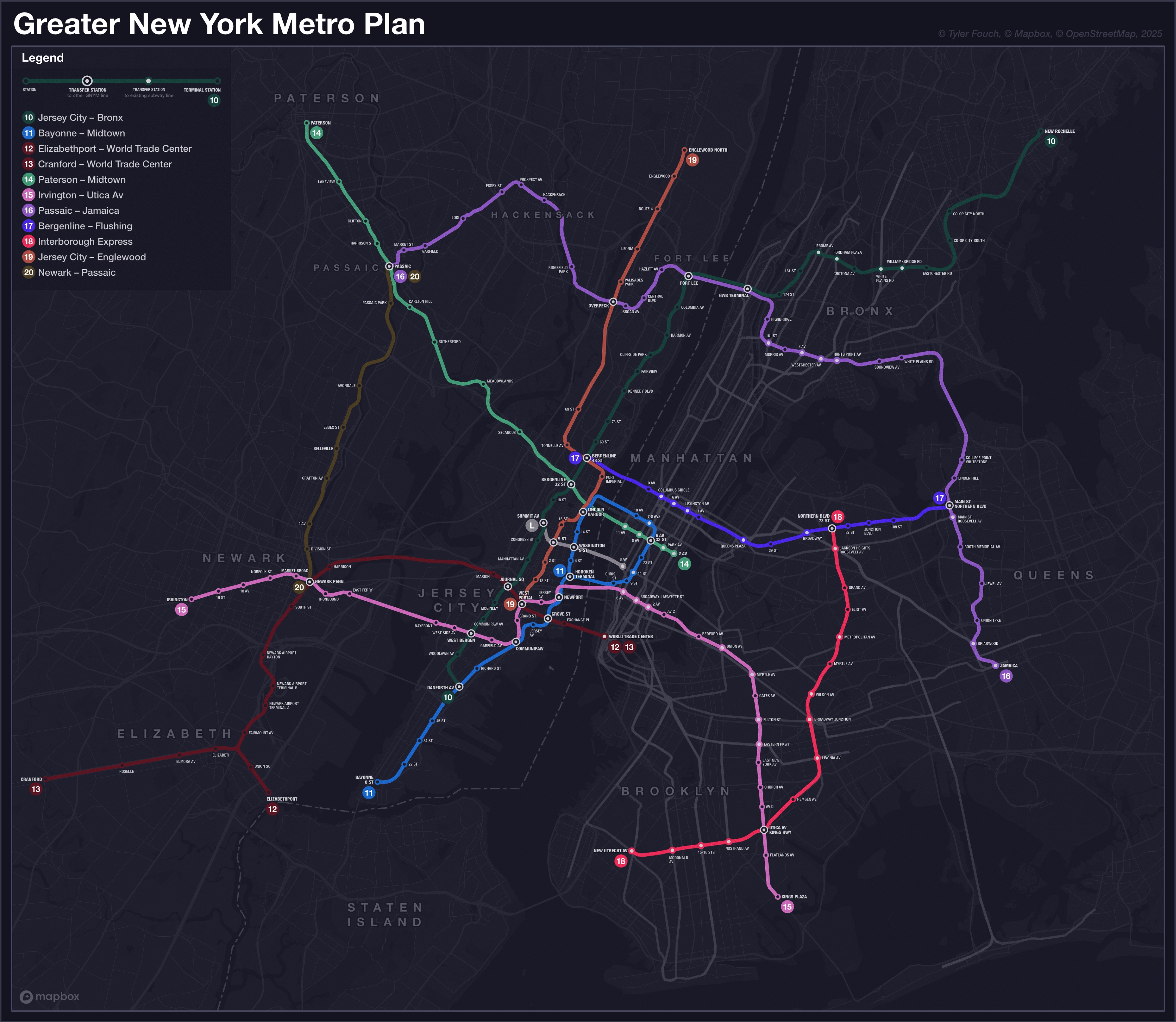

This series will outline a plan for a new network of rapid transit lines designed to serve both high-demand corridors and areas I’ve classified as high-quality transit deserts. While northern New Jersey is the primary focus, the plan also addresses critical rapid transit gaps within the five boroughs, especially in parts of Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx.

These lines should follow modern metro standards: automated trains, smaller-scale (less costly) construction, and shorter trains, balanced out by very high service frequency (enabled by automation) to provide needed capacity. There should be full fare integration with MTA subway lines and buses as well as NJ Transit buses, allowing free transfers throughout the network. People shouldn’t have to pay twice just because they crossed a border. Furthermore, interlining will be avoided in order to reduce complexity and potential for delays (one of the NYC subway’s biggest pitfalls), and stop spacing will be longer — increasing train speed and reducing overall construction cost.

The goal is not just to build new lines and extensions, but to build a truly convenient and connected system. To support key decisions within this plan — like station locations, route alignments, and proposed service frequencies — with actual data, I developed a multiple regression model in Python to estimate rapid transit ridership at any location within the New York City region. This model draws on several factors, including population density, job density, distance to Midtown Manhattan, the amount of service the station receives or might receive, and more. I also analyzed the busiest bus corridors and most densely-populated under-served areas to help determine which should and shouldn’t be served by heavy rail mass transit.

While this plan mainly focuses on new-build lines, it also assumes the completion of some key MTA projects that should be pursued. This includes finishing the Second Avenue Subway (with its currently planned Q and T train service plans), extending the Q train west across 125 St, continuing the T train north into the Bronx along Third Av, and extending the M train as detailed in the QueensLink proposal.

One might argue that these projects belong within the Greater New York Metro Plan (GNYM), but as extensions of the existing subway network, they are quite different in scope and construction and are moreso complementary to the plan.

A detailed map of the plan is included below:

Let’s walk through the plan.

Bergenline Avenue and Beyond

Line 10 will provide much-needed heavy rail rapid transit service along the north–south Jersey City–Bergenline Avenue–Fort Lee corridor, starting at Danforth Avenue in Greenville and running north through Hudson and Bergen Counties, into Manhattan via the George Washington Bridge, and across the Bronx to Co-Op City and New Rochelle. It will connect with multiple lines in the GNYM plan, an extension of the L train (also part of this plan), and existing NYC subway lines — serving dense urban neighborhoods and improving regional and orbital connectivity.

PATH and HBLR

The PATH network will be de-interlined and merged into the GNYM network to reduce complexity. The Journal Square–33 St service will be mostly replaced by Line 11, which will also take over the Bayonne branch of the HBLR. Line 11 will follow a new route through downtown Jersey City to a new station at Hoboken Terminal, then use a new tunnel from Hoboken to Manhattan — eliminating the awkward stub end at Hoboken Terminal. In Manhattan, it will follow the current route, then extend north and then west, before looping back south into Hoboken along Washington St and terminating at Hoboken Terminal (with a transfer to itself).

The Newark–World Trade Center service will stay mostly the same, but extend to Newark Airport. After, it will split: Line 12 will head to Elizabethport while Line 13 will head to downtown Elizabeth and then Cranford.

Line 15 will use PATH’s existing Uptown Hudson Tubes, which will be freed up by Line 11’s routing along a new tunnel from Hoboken. It will provide an another route between Newark and Jersey City, serving additional neighborhoods in both cities. It will also take over the West Side branch of the HBLR. The line will continue into Lower Manhattan and extend into Brooklyn towards and along Utica Avenue, a heavily used bus corridor that has long been proposed for rapid transit.

Line 18 will complete the takeover of the HBLR system, assuming its northern section. It will begin at West Portal, a new transfer hub just west of the portal for the PATH tunnels in Jersey City — between the current Journal Square and Grove Street PATH stations — with connections to Lines 12, 13, and 15. The line will travel along a mix of active and disused freight rail rights-of-way before joining the current HBLR alignment in Hoboken. From the HBLR’s current northern terminus at Tonnelle Avenue, it will extend north along freight right-of-way to Englewood, fulfilling an original promise of the HBLR to extend into Bergen County.

Paterson and Passaic

Line 14 will connect Paterson to Midtown with a fast and direct route. It will use a new tunnel under the Hudson and provide a key transfer to Line 10 at 32nd St in Union City. Additionally, it will offer direct access from Manhattan to the Meadowlands Sports Complex (MetLife Stadium) and the American Dream Mall — much more convenient for events than the current NJ Transit Meadowlands service. The line will follow the historic Erie Main Line right-of-way through Passaic and Clifton, before terminating at the current Paterson NJ Transit station.

Cross-Hudson Relief

Line 17 wasn’t part of the original plan, but emerged as a strategic addition to provide important redundancy and reduce transfer congestion. It was created after I realized that the Bergenline Av/32 St station, where Lines 10 and 14 intersect, would likely see extremely high transfer volumes due to Midtown-bound demand. Line 17 would help disperse that pressure, offering an alternate route to Midtown Manhattan. It will serve northern Midtown, then continue into Queens, running parallel to the 7 Train all the way to Flushing, relieving strain on one of the city’s busiest lines.

The L Train will be extended west across the Hudson River, through Hoboken, before terminating at a transfer with Line 10 on the border between Jersey City and Union City. It will intersect with Lines 11 and 19 as well. Similar to the idea behind Line 17, this extension should relieve pressure on other cross-Hudson routes by providing another connection to Manhattan. It will also create a valuable east–west link within Hoboken and strengthen access to the important 14 St corridor in Manhattan.

Orbital Lines

Line 16 will bring Hackensack into the system and provide needed orbital connections, enabling travel between Passaic, Essex, and Bergen Counties, Upper Manhattan, and the Bronx without having to pass through Midtown. In the Bronx and Queens, it continues this orbital role. It acts as a crosstown line in the South Bronx and serves the Lafayette Av corridor (presently a transit desert). The line then crosses into Queens, connecting Flushing and Jamaica (both major Queens hubs) via Main St.

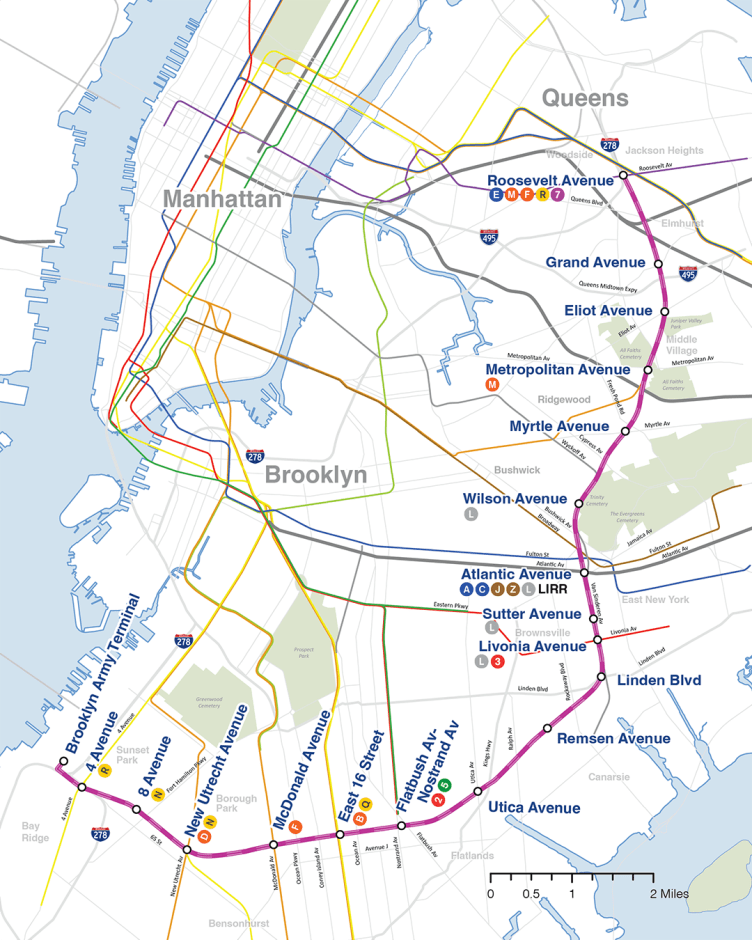

Line 18 will be a rapid transit conversion of the currently-proposed Interborough Express light rail line, with upgrades to GNYM standards and realignments for better transfers, and a northern extension to meet Line 17 in Jackson Heights.

Line 20 will connect Newark and Passaic, following the Passaic River along a mix of elevated structures, freight rail corridors, and freeway rights-of-way. With connections to major transfer hubs at both ends, it enables direct travel between Newark, Passaic, and Paterson without having to go into central areas just to head back out.

Conclusion

Of course, an ambitious plan like this would face many obstacles. Cost is perhaps the most obvious of them, especially with today’s sky-high construction costs. There is also the matter of cooperation needed between many different actors within the region (the MTA, Port Authority, NJ Transit, etc.) in order to execute the plan. I’m no expert on policy, so I can’t speak to what should be done about these issues. But what’s clear to me is that the status quo is not an option anymore: at this point, it’s holding back the progress that the region so urgently needs. With the Greater New York Metro plan, both New York City and northern New Jersey can gain a faster, more convenient, and more interconnected rapid transit system — one that truly matches the region’s scale and importance.

Leave a comment